News

Dr Ben Cowell, Director General, Historic Houses

Congratulations from the Thoroton Society to Dr Ben Cowell, who was appointed OBE in the New Year’s (2021) Honours List. Ben did his first degree at the University of East Anglia, but for his Ph.D he moved to Nottingham where he was supervised by myself, and Professors Steve Daniels and Charles Watkins. In 1997 Ben gave the Nottinghamshire History lecture to the Thoroton Society on ‘The Politics of Park Management in Nottinghamshire, c.1750-1850’. This was published in Transactions, volume 101 (1997), 133-44. With his Ph.D safely banked, Ben left Nottingham and worked for English Heritage, the National Trust, and the Department of Culture, Media and Sport, before moving to his current post as Director General of the Historic Houses Association which represents over 1,600 important country houses in independent ownership. He has also published several books, including one entitled The Heritage Obsession. Unsurprisingly, Ben has been particularly busy through 2020 and into 2021 because of the need to keep occupants safe through the coronavirus pandemic. Hopefully, we will be able to invite him back to speak to the society before too long.

John Beckett

New Member of the Thoroton Society and the Thoroton Research Group

Dr Andrea Moneta of Nottingham Trent University. Andrea is a member of Global Heritage research group and Artistic Research Centre at Nottingham Trent University. His research interests include: Nottingham, the City of Two Towns; mapping the Wall of French and English Boroughs through creative technologies to foster a link between local heritage and community engagement; workhouses and the development of creative interpretation of welfare heritage; Design for Heritage at The Nottingham Castle

John Wilson

Early Members of the Thoroton Society

2022 sees the 125th anniversary of the founding of the Thoroton Society. It is of interest to look back at our early members, particularly those who can be regarded as Founder Members, who attended (or sent apologies for) the inaugural meeting in 1897. Some went on to be significant names in the history of the Society. Others were faithful, if relatively undistinguished, members for many years. Up until 1958, the Society in fact published the names and addresses of all members in the annual Transactions (unthinkable nowadays with data protection concerns).

I have prepared a database of early members who were in membership for a significant number of years, to act as a resource for future research. Hopefully, we will have the biography of an Early Member, so far as it can be traced, in each issue of the Newsletter (Editor permitting!) for the foreseeable future. Professor Beckett set the ball rolling in the recent Winter issue with a fine study of the life of Cornelius Brown. If any member would be interested in participating, and researching the life of an early Thorotonian, please contact me and I will send a copy of the list from which you can choose a person to research.

John Wilson treasurer@thorotonsociety.org.uk

ARCHAEOLOGY DISCOVERIES IN NOTTINGHAM NEW AND OLD

A New Cave (2020)

In the summer 2020 newsletter it was reported that a possible cave had been discovered in Nottingham but that investigations had been put on hold due to the global pandemic. The feature was discovered when, due to very heavy rain early in the year, a sink hole appeared in the rear garden of the property. This had exposed a rock-cut shaft, with tool marks visible, which was roughly square shaped in plan. A large amount of the garden above had disappeared into the shaft, raising the possibility this was a cave and not simply a deeply cut pit.

The site is at the rear of a property on Friar Lane, although specific location details cannot be revealed at this time. In December the collapsed material was removed and this revealed a chamber leading off the shaft, in the opposite direction to Friar Lane, at a depth of approximately 4m below ground level. Historic maps do not provide any clues as to why a cave of this uncommon type should exist at this location. The cave must predate the 19th century building at the site, given the position of the shaft, and is probably much older than the 19th century. Documentary research will take place in the coming weeks. Unfortunately, due to the depth, and the position of the chamber, the cave could not be investigated further. However, discussions between the site owner, a structural engineer and myself enabled a solution to be found to ensure that the cave is fully protected whilst allowing the ground, and services, to be reinstated in a safe manner. The shaft will be backfilled with loose granular material and, at a level above the cave, will be capped with concrete. This will mean that should the opportunity arise in the future it will be possible to once again expose the entrance to the cave chamber. It is really encouraging that engineering solutions can be found which enable caves to be preserved whilst enabling works to be completed. Over the past few years I have worked with developers and engineers to ensure that caves are preserved and it is heartening to see such a huge change from the times when caves were all too frequently filled with concrete. With the City Council’s new caves policy and forthcoming guidance for cave owners, the future of these important parts of our heritage looks much brighter.

Caves have, on a small number of occasions, been the cause of sink holes and so each time a sink hole appears I try to investigate. At least two have been reported in the Nottingham Post this year, including one on High Pavement and a second on South Sherwood Street (the latter reported in December 2020). Neither of these sink holes involved caves.

The Water Cave (1936)

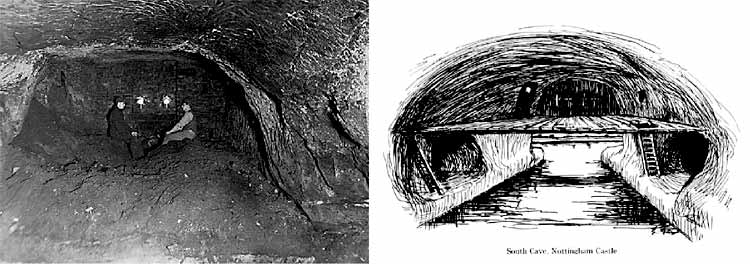

Two Images of the Water Cave provided by Scott Lomax: photograph taken in 1935 (left) and Campion's vision of the Water Cave (right).

There is a cave at the foot of the Castle Rock, which despite being next to Mortimer's Hole, is relatively little known. The cave is known today as the Water Cave, for reasons which will soon become clear. At the time of its discovery in 1936 it was named the South Cave. The cave was discovered in circumstances that attracted great interest. George Campion, who was Director of the Thoroton Society Excavation Section, had been undertaking excavations at and around the castle for a number of years. That same year he had led investigations at the Western Passage and the Northwestern Passage.

In February 1937, when excavation had been completed, Campion told The Nottingham Journal that on three successive days he had what he described as a vivid dream in which he saw a cave at the foot of the Castle Rock. The dreams encouraged him to excavate at a specific location and upon digging into the ground he revealed a cavity in the rock. Campion was keen to point out that his dream was not some sort of psychic experience, but instead that he had always suspected there might be a cave at that location and having spent so much time thinking about the castle and its caves he inevitably dreamt about it.

Campion and his fellow amateur archaeologists were assisted in excavating the cave by staff from Nottingham Castle. Upon full excavation a chamber was found to measure approximately 12m in length, 5m in width and 7m in height. Holes in the sides of the chamber provided evidence of a timber platform. Passages were found on either side of the chamber, running in the directions of Mortimer's Hole and the Western Passage. Unfortunately this cave, which is of medieval date, is now largely inaccessible. When discovered it was remarked that the cave floor was approximately 2m below the River Leen (Castle Boulevard largely follows the course of the Leen). Being below the water table the cave is flooded. It was because the area was prone to flooding that the land at the base of the Castle Rock was substantially raised, thereby hiding all trace of the cave. Mediaeval pottery in the lower fill of the cave seemed to suggest the cave was partially filled during that period.

The cave appears to have been accessible, at least in part, during the 17th century. Lucy Hutchinson, wife of Colonel John Hutchinson (Parliamentarian Governor of the town of Nottingham during the Civil War) wrote in her memoirs of her husband that there was a spring, which was known as Mortimer's Well, near to Mortimer's Hole. This must have been the cave we know today as the Water Cave. Campion believed the cave was a boathouse, whereby boats would travel along the River Leen and sail into the cave where goods they were carrying could be unloaded. If Campion was correct then there must have been a significant diversion of the River Leen at the foot of the Castle Rock, or a manmade channel leading from the river to the cave. Certainly, there was a channel excavated to divert water from the Leen in order to power the mills that once stood in the Brewhouse Yard area but due to limited archaeological work in this area it is not known whether boats could get close to the Castle Rock, let alone enter into a cave.

Unfortunately, we cannot know whether Campion was right, although future archaeological work in this area, should any excavation be undertaken, could shed some light on the function of this cave and its undoubted important role in the servicing of the medieval castle.

Scott Lomax, Nottingham City Archaeologist

Tales from the River: an Enigmatic Wooden Structure from Cromwell Quarry

In July 2020 Trent and Peak Archaeology was commissioned by The Guildhouse Consultancy on behalf of Cemex to undertake the excavation of a wooden structure. As part of ongoing archaeological monitoring at the quarry, a large palaeochannel was recorded which contained the remains of a substantial linear wooden structure (Plate 1). The channel is located c. 750m south of a Roman villa complex and c.800m NNE of the location of an 8th century bridge over the River Trent (Salisbury 1995). The palaeochannel sequence comprised basal sands and gravels overlain by buff-brown to orange-brown sands with interbedded clays sealed by 2-3m of overbank alluvial silt and clay.

The enigmatic wooden structure was defined by two rows of large posts driven into the underlying sand and gravels along the left bank of the channel edge. Between these posts were the remains of at least two if not three wattle panels (Plate 2). These elements were extremely fragile and excavation progressed rapidly due to the often hot and dry weather conditions. The wattle has yet to undergo identification, but it is likely to be either hazel or willow as these species have the necessary flexibility and length to be woven into sturdy panels.

Within the channel sediments, multiple unused or displaced upright timbers were recorded (Plate 3). These offer a valuable insight into the structure as they may indicate the full uneroded lengths of the uprights. In addition to the driven posts, large jointed timbers were located offset to the main post alignment and were anchored into the base of the channel by upright posts (Plates 4 and 5). The main upright timbers showed evidence of slumping which may have caused part of the main structure to collapse. This may be due to processes associated with the lateral migration of the channel or to increases in channel energy over time. The presence of large jointed timbers perpendicular to the main structure has led to the suggestion that this may represent a pier-like construction. The upper two thirds of these jointed arrangements have been eroded away and therefore exactly how these elements tied into the main alignment of wattle and posts is unclear. Tantalisingly, several timber items, which have been interpreted provisionally as belonging to sewn plank boats, were also recovered. It is tempting to suggest that the structure represents a possible mooring point within an active, high energy channel.

The remains recorded here probably represent only a third of the original structure. None of the superstructure, which may have lain above the water line, was preserved. In addition, no large blocks of stone, commonly associated with fish weirs and bank stabilisation, were found during excavation. In consequence, the structure remains open to interpretation.

A single radiocarbon age determination of 688-882 cal AD (BETA-564739, 1230+/-30 BP) from elements of the structure, as well as an 8th century dress pin located within the channel deposits, provide provisional evidence for a broad Anglo-Saxon date for the structure. It is hoped that some of the timbers may be suitable for dendrochronological dating and that further radiocarbon samples will be submitted. A detailed programme of post-excavation and palaeoenvironmental analysis is forthcoming and it is hoped that this will provide further insights into the character of the structure and the surrounding landscape.

Reference:

Salisbury, C. 1995 ‘An 8th century Mercian bridge over the Trent at Cromwell, Nottinghamshire, England’. Antiquity 69. 1015-18.

Plates

Plate 1: Long upright post rows aligned along the edge of a channel.

Plate 2: Fragments of fragile wattle panel. Plate 3: Unused or displaced upright timber.

Plate 4: Mortise joint with upright securing post.

Tom Keyworth and Kristina Krawiec, Trent & Peak Archaeology

TWO IMPORTANT CENTENARIES THIS YEAR

'Major Oak' by Andrew MacCallum.

The artist Andrew MacCallum was born in 1821 - he painted many landscapes including the one of Sherwood Forest shown here.

Even more important is that in 1521 Anne Ayscough (erroneously spelled Askew) was born. She was closely associated with many of the dissident families in Nottinghamshire and she was also a writer and poet, writing in English, and a Protestant martyr who was condemned as a heretic in England in the reign of Henry VIII. She was tortured in the Tower of London and burnt at the stake on 16th July 1546.

Barbara Cast