Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Short articles by Terry Fry

Dr. William Stiff a.k.a. Phillimore

In his after lunch talk to members of the Thoroton Society at Kelham Hall, Noel Osborne mentioned that the father of William Phillimore Watts Phillimore was Dr. William Stiff.

In April 1855 Dr. Stiff was appointed Resident Medical Officer and Superintendent of the General Lunatic Asylum, Nottingham (now the site of King Edward Park on Carlton Road). He was highly regarded, receiving a pay rise of £150 p.a. in 1864, and remained in office until his death in November 1881. Then, the Asylum Committee said it ‘had lost a faithful and zealous officer, the Asylum a true friend’. He had changed his name to Phillimore in 1873 by Royal Licence. He was also President of Bromley House Library in his final year.

The photograph on the right shows him and his wife and three children in the garden of the Superintendent’s house on Windmill Hill (now Lane), which was specially built for him sometime in the early 1870’s. (Oaklands Mill is to the right). Before that he had to make do with a cottage next to the Asylum mortuary, which may have influenced his decision to change his name! With his top hat and full set of whiskers Dr. Stiff/Phillimore resembles President Abraham Lincoln - or is it W. G. Grace? One of the boys in the photo is thought to be William Phillimore Watts Phillimore, the famous genealogist and founder of the Phillimore Publishing Company, of whom Noel Osborne spoke so eloquently.

The boy was born at a house on Villa Road, Nottingham on 27 October 1853, the son of William Phillimore Stiff and Mary Elizabeth Stiff née Watts. She was the daughter of Benjamin Watts of Brigden Hall, Bridgnorth. The Stiffs and Phillimores were both old families of clothiers resident for many generations in Cam, Gloucestershire. (Dr. Stiff’s great grandfather, Thomas Stiff, had married Ann Phillimore at Cam). When he died in April 1913, W.P.W. Phillimore was buried at Bridgnorth, suggesting an important connection with his mother’s family.

Nottingham Celebrates Napoleon’s Defeat in 1814

There will be many events this year commemorating the outbreak of the Great War in 1914. By contrast exactly a hundred years earlier amazing celebrations accompanied the end of the long-drawn-out Napoleonic Wars in 1814.

On 15 April the Nottingham Journal reported the enthusiastic delight of everyone on hearing of ‘Bonaparte’s dethronement’ on 4 April. Crowds turned out to welcome the coach, decorated with laurel and flags, which brought the good news. Church bells rang for two days, a huge bonfire was lit in the Market Place, and the incessant firing of guns was deafening. The Nottingham Date Book noted ‘Ninety gentlemen of the first respectability dined together at Thurland Hall and others, both Whig and Tory, at the principal inns. At night there was a pretty general illumination’. But not for everyone. The Journal reported that Mr. G. Hopkinson of Long Row did not illuminate his shop so three balls were fired through his window. For the same ‘offence’ someone else fired a shot through the keyhole of Mr. White’s house in Stoney Street.

However there was another and universal illumination of the town, following the definitive treaty of peace in June. The Council agreed to foot the bill for illuminating the Exchange building, the Guildhall and the Police Office. (The total cost was at least £159, or possibly £8,000 to £9,000 today). The ‘transparencies so masterly painted by Bonnington [Richard Bonnington Senior] which ornamented the front of the Exchange eclipsed everything else’, according to the Journal. Bonington was paid £30. The complete scheme was arranged by Edward Stavely, the Town Surveyor and Architect.

The front windows of the Exchange were decorated with fifteen transparencies, showing images of Wellington, Nelson, King Alfred, Blucher, the Prince Regent, Louis XVIII and others. Smith’s Bank was more adventurous and showed a Cossack on horseback thrusting Bonaparte into the jaws of a monster. The Nottingham Journal office bore a prosaic figure of Britannia but the Nottingham Review amused spectators with a transparency showing ‘John Bull burning the Income or rather the Inquisitorial Tax’. The Castle was brilliantly lit at every window, with flambeaux (torches) on the parapet wall matching over 200 flambeaux on the Exchange. These, together with the masses of candles being lit, must have presented a great risk of fire, especially as nearly the whole population spent most of the night on the streets or in pubs.

Sadly the celebrations proved to be premature and Napoleon had to be beaten again at Waterloo in June 1815. But there were no public celebrations in Nottingham that time.

Balloonacy

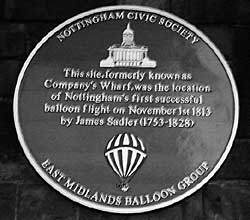

Following my article Balloonacy in Issue 73 of the Newsletter last autumn it is a pleasure to record that a plaque referring to James Sadler’s ascent was unveiled on 30 November 2013. It was erected next to the entrance to the Fellows, Morton and Clayton pub on Canal Street. The Nottingham Civic Society paid for it to be put up, but footing the bill for its manufacture was the East Midlands Balloon Group.

The wording on the plaque is:-

This site, formerly known as

Company’s Wharf, was the location

of Nottingham’s first successful

balloon flight on November 1st 1813

by James Sadler (1753-1828)

< Previous