Articles from the Thoroton Society Newsletter

Six pots and donor discovered

By Nick Molyneux

Photo: Mark Laurie / Courtesy of University of Nottingham and Lincolnshire County Council

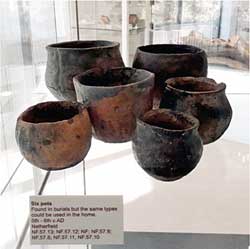

Photo: Mark Laurie / Courtesy of University of Nottingham and Lincolnshire County CouncilNottinghamshire’s Historic Environment Record (HER) entry [M8927] suggests that our Anglo-Saxon forebears established a cremation cemetery in what is now the Netherfield area of Carlton, close to the River Trent and just downstream from Nottingham. There are six known pots which survive and these now reside in the University of Nottingham’s Museum of Archaeology. The HER helpfully advises that a number of noted Anglo-Saxonists of the mid-20th century published information or commented on the pots and the existence of the cemetery. However, despite these references, what is not so clear today is where the pots were found, when the discovery occurred or in what context the finds were made.

Lincoln City & County Museum: Although now in Nottingham, the pots were originally donated to Lincoln City and County Museum in 1912 along with a number of other items. Very brief details may be viewed online at the wittily-named Lincs to the Past website by searching on “Netherfield”:

Reference |

Description |

LCNCC: 1912.311 to |

Ceramic: Early British pottery (six pieces one inside another), Trent Valley, Netherfield, UK |

LCNCC: 1912.317 |

Axe: Three polished stone celts, Trent Valley, Netherfield, UK |

LCNCC: 1912.318 to |

Ceramic: Early British pottery (six pieces one inside another), Trent Valley, Netherfield, UK |

There is something of an anomaly here. There appear to be eight ceramic artefacts for the six pots. Perhaps there has been some misclassification? Once broken pieces now repaired? Or are there a couple of other pots somewhere? The pots are surprisingly small and rather plain. On the face of it, it is hard to see them as cremation urns. They are certainly not of the larger, decorated types one might readily associate with some Anglo-Saxon cremation cemeteries. As Mark Laurie’s photo of the pots on display in Nottingham shows, there is a distinctly domestic look to them. But that need not exclude the possibility that they came from one or more cremation burials. A separate piece of work has been undertaken to document the pots themselves and if it is of interest to members of the Thoroton Society, details may be included in a future Newsletter.

The Anglo-Saxonists: At some stage the prevailing view as to the identity of the pots shifted from “Early British” to Anglo-Saxon. The first dated reference in the HER is the 23rd of October 1932 and is a personal comment from the noted Southwell-born Anglo-Saxon scholar, Sir Frank Stenton. Unfortunately, the HER does not record what Sir Frank’s comments were. An undated personal comment is also noted from C.W. Phillips re “OS Rec 6in”. Charles William Phillips was involved in the 1939 excavation of the ship burial at Sutton Hoo and became head of the Archaeology Branch of the Ordnance Survey. He is also credited as a contributor to the Ordnance Survey’s 1939 publication, the Map of Britain in the Dark Ages (South Sheet). This map shows a symbol for a “single burial” just to the east of Nottingham and opposite the symbol for a “cemetery” immediately to the south, across the River Trent, which is presumably the cemetery at Holme Pierrepont. Could this “single burial” represent the Netherfield site? There are two other published references which the researcher may follow, an entry in Audrey Meaney’s 1964 A Gazetteer of Early Anglo-Saxon Burial Sites and a drawing of each pot in J.N.L. Myres A Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Pottery of the Pagan Period (1977). Yet none of these explain the when, where and why of the discovery of the pots.

The Museum Guide: The Collection has a helpful on-line resources section, which includes a scanned copy of a 1913 Museum Guide by the curator, Arthur Smith. At the end of the guide, page 13 gives what appears to be an incomplete alphabetical list of donors ending in the letter “N”, the rest presumably originally on a now missing page 14. If the pots had been given in 1912, might the donor have been included in that list?

The Donor: After another trawl through its records, The Collection advised that it had some additional information. The pots were received on the 20th December 1912. The identity of the donor was confirmed as one Dr. Alexander Fraser and sure enough his name appeared in the surviving portion of the 1913 list of donors. A quick look at Kelly’s Directory of Nottinghamshire 1904 confirmed that a surgeon of the same name resided at an address on Burton Road in Carlton. This certainly seemed like the right person in the right place at the right time.

The Early Years: Alexander Fraser was born in Dingwall in early September 1858. His medical school records record the date as 9th of September 1858, whereas on-line records suggest the 4th of the month. His father was a tailor. His schooling prior to medical school was Dingwall Free School, 2 years; Tain Free School, 1 year; Invergordon High School, 6 years; High School Edinburgh,1 year and a half. At some stage his family moved to nearby Strathpeffer, a holiday boom-town of the Victorian romance with all things Scottish. It was also the site of a number of medieval clan battles and the famous carved Pictish monument, the Eagle Stone. If ever there was a place which might inspire an interest in the past, Fraser’s childhood home was certainly it.

Medical School: According to records at Edinburgh’s Medical School, Fraser began studying Medicine at Edinburgh University in the academic year 1875-76 and he graduated with an M.B. Edin, C.M. (Bachelor of Medicine (Edinburgh), Master of Surgery) in 1884. This was a general medical degree, qualifying the holder to practise as a doctor. At the start of his studies in Edinburgh, Fraser’s records show that he was living at 10 Buccleuch Place and at the time of his final exams he was at 13 East Preston Street. He would have been a contemporary of Arthur Conan Doyle, who studied Medicine at Edinburgh between 1876 and 1881.

Twickenham Park: Following graduation, Fraser appears to have been in practice at Twickenham Park in south west London. It seems likely that it was here he met his future wife Emily, her father being a civil engineer living in Twickenham.

Carlton, Nottinghamshire: The 1891 census returns show Fraser living at Burton Road, Carlton, where he is described as a single “medical man and general practitioner” with a household consisting of a housemaid/domestic servant and a coachman/domestic servant. In 1893 he married Emily Marianne Codrington at Brentford and the 1901 census has Fraser still living on Burton Road, described as physician and surgeon. His household consists of his wife Emily, three daughters, a domestic cook, a domestic nurse, and a domestic housemaid. Despite his collection of artefacts, Fraser does not appear in the early membership lists of the Thoroton Society and nor was he a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London.

Caistor, Lincolnshire: In 1910, Fraser bought a medical practice in Caistor, Lincolnshire from the estate of a recently deceased GP, Dr. Francis R.S. Gaman. He was appointed Medical Officer and Public Vaccinator for Caistor (No 1) District. The 1911 census shows him living at Caistor House, in the centre of Caistor, as a medical man and MD. His household consists of two daughters, one son, a governess, a domestic housemaid, a domestic cook and a domestic nurse. (His wife and one daughter were visiting her parents in Twickenham when the census was taken.) Also living there was his unmarried brother-in-law, William J Codrington, aged 40 and described as medical man and MD. In the same year he was elected a member of the Lincolnshire Automobile Club and was a member of the United Ancient Order of Druids. In 1929 he became a Justice of the Peace and in 1932 was appointed Medical Officer for the then newly-formed Lindsey and Lincoln Joint Smallpox Hospital Board. The 1939 National Register shows him living at Caistor House, Caistor, and describes him as physician and surgeon. The household now consisted of his wife and an unmarried daughter.

The Donation: In December 1912, Fraser donated a collection of Early British artefacts to the Lincoln City and County Museum. The 1913 Museum Guide refers to them as:

“Case 1. Contains a fine group of Early British pottery. The greater number of these have been deposited by Mr. H. Preston, F.G.S.; others are the gifts of various donors. All of them have been found in Lincolnshire. Dr. Alexander Fraser’s collection of Early British pottery and implements have been recently deposited in this case."

The Grantham Journal of the 28th of December 1912 has more to say:

“PREHISTORIC POTTERY - TRENT VALLEY FINDS FOR LINCOLN MUSEUM. Dr. Alexander Fraser, of Caistor, has deposited his collection of prehistoric pottery and stone implements in the County Museum at Lincoln. They were all found in the Trent valley, and are fraught with great interest. The pottery is of very early type, being undecorated and of simple form. There are six vessels. The largest is about five inches in height, and has a small cup inside. When found, this urn was covered by a sort of mosaic of pebbles, which made an effective cover of unusual form. The other vessels vary in size from 3in. to 4.5in. in height. There are three fine polished celts of a greenish-coloured compact stone. The largest is 12in. long, another is 10in. and the smallest is over 8in. There are also three implements of a granite-like stone. There is already on exhibition through the Museum a fine series of British pottery, dating back some three thousand years, and the addition of Dr. Fraser’s specimens makes it all the more complete and interesting.’’

So, in 1912 the pots were not recognised as being Anglo-Saxon, perhaps because of the lack of ornamentation and their association with the earlier stone implements.

Obituary: Alexander Fraser died in Caistor House on the 27th July 1942 and was buried at St. Luke’s, Holton Le Moor, Lincolnshire where his headstone reads “Physician, husband of Emily Marianne Fraser”. According to Fraser’s obituary in the Lincolnshire Echo (29th July 1942), he was the Medical Officer of Health, Caistor Rural District; Medical Officer to North East Lindsey Joint Hospital Board and Medical Officer to Lindsey and Lincoln Joint Smallpox Hospital Board - all three appointments he held up to his death. It was also noted that he was “a keen archaeologist, and a student of the geology of the Lincolnshire Wolds” and that “in both subjects pursued an independent line of inquiry.” This independence may explain why he was not a member of either the Thoroton Society or the Society of Antiquaries. His obituary notes that he was survived by his wife, three daughters and his son, Dr. A.C. Fraser, who had a practice in Lincoln prior to war service with the RAF. A later reference in the same paper (15th September 1942) regarding the auction of his possessions after his death included the sale of John Wesley’s rocking chair! Emily died in 1947 in Cuckfield, Sussex.

Transfer to Nottingham: In 1957, the pots and implements were transferred to the University of Nottingham on loan where they may be viewed today. The University has no surviving accession records but it seems likely that the City & County Museum’s focus on items from within the County of Lincolnshire made the transfer to an establishment more local to the find spot a logical move.

Further Work: So, at least the donation of these pots and other artefacts is now a little better understood. The find spot and circumstances in which the pots were discovered are still unclear and work is on-going to resolve this. It is hoped that further information may be shared along with details of the pots themselves in future issues of the Thoroton Newsletter.

If anyone has any information regarding the Netherfield Anglo-Saxon cemetery, please e-mail details to: n.molyneux@live.co.uk.

With thanks to: Eleanor Baumber, Collections Development Manager, Lincolnshire Heritage Service & Archives; Alan Dennis, The Caistor Heritage Trust; Terry Hanstock, Genealogical Correspondent, Nottingham Drinker; Mark Laurie, University of Nottingham Museum of Archaeology; Kevin Leahy, Portable Antiquities Scheme; Andy Nicholson, Nottingham History website (http://www.nottshistorv.orq.uk/): Claire Pickersgill, University of Nottingham Museum of Archaeology; Heather Rowland, Society of Antiquaries of London. Danielle Spittle, Edinburgh University Library; Professor Moira Whyte, College of Medicine and Veterinary Medicine, Edinburgh; Professor Howard Williams, University of Chester.

Sources: 1891, 1911 Census; 1939 National Register; Daily Mail [Hull] (8th March 1929); Grantham Journal (15th April 1911 & 28th December 1912); Kelly’s Directory of Nottinghamshire 1904; Lincs to the Past website (https://www.lincstothepast.com/); Lincoln City & County Museum Publication No. 15, Museum Guide, May 1912 by Arthur Smith; Lincolnshire Echo (16th March 1911, 29th July 1942 & 15th September 1942); Louth & North Lincolnshire Advertiser (30th April 1910); More Portraits of Caistor Lincolnshire” 2007 by Rev. David Saunders; Nottingham Evening Post (18th November 1932); Map of Britain in the Dark Ages (South Sheet), Ordnance Survey, Southampton 1939; The Lincoln, Rutland, and Stamford Mercury (15th July 1910).

< Previous