Book reviews, Spring 2016

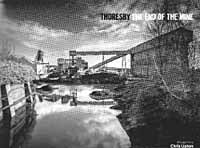

Thoresby: the end of the mine

This is a large format 32x24 cms, softback, 140 page book dealing with the period of closure of Thoresby Colliery, the last deep mine in Nottinghamshire. It is primarily a photographic record of the closure period with quotes from workers to augment the images. The author, Chris Upton, is a professional landscape and documentary photographer working out of Southwell. He is an official Fuji X series photographer and has worked, amongst other things, for the Thai Tourism Authority in making images of Thailand for tourist advertising purposes.

Chris was given access to the colliery site and was able to document the surface activities, offices, workshops, stores and the colliery in general. A particularly poignant section contains portraits of several of the workers at Thoresby. The images are all monochrome, photographed and reproduced in exceptionally high quality.

This is a very important document in the history of Nottinghamshire, particularly the coal industry, and is well worth the purchase price for the photographs alone. However, it is also of importance to any local historian of Nottinghamshire as well as anyone who is interested in the story of the County.

The book is highly recommended. It costs £25 plus p&p obtained directly from the author's website at: www.chrisuptonphotography.com/section807424.html.

Howard Fisher

Bonnie Prince Charlie and The Highland Army in Derby by Brian Stone

Cromford, Scarthin Books, 2015.pp207. ISBN 978-1-900446-16-7 pbk £12.95

This is a highly enjoyable book which deserves a wide readership. Its main purpose is to explore the brief occupation of Derby by Prince Charles's army in December 1745. The occupation is set into a detailed context of the history of the Stuarts, the rebellion, local and national politics and finally the invasion itself: this takes up the first five of the twelve chapters of the book before it turns to the central topic, the prince and his army in Derby. Brian Stone has made extensive use of available primary sources in order to explore the effects on the town of the presence of the invading force as well as examining some of the myths surrounding the occupation, both contemporary and those developed since. Stone explores how the town was abandoned by numerous of the more prosperous inhabitants and by the Derby Blue regiment which marched to Nottingham during the night of 3-4th December when it was realised that they alone were in the path of the prince's advancing army. Once at Nottingham, they were given control of the Nottinghamshire county magazine at the castle.

One of the strengths of the book is the vivid way in which mid-eighteenth century Derby is presented; this brings the town and its inhabitants to life and thus in turn makes the occupation real. Stone tackles the inhabitants' perceptions of the Highland Army and attempts successfully to show how the image of rough and uncouth highlanders presented by the national press was offset by some of the eye witnesses and by those whom the soldiers were billeted upon. He also explores in some detail the decision to withdraw from Derby, made on 5th December at what has reportedly been a stormy council of war at Exeter House. The book concludes with several chapters exploring the retreat and the conclusion of the rebellion with a final chapter reviewing Charles Stuart's chances of success had he advanced towards London instead of retreating. Brian Stone has included a series of useful and interesting appendices, including an analysis of the army led by the prince into Derby. Whilst the book naturally focuses on neighbouring Derby it is an important study of an event of national and international importance through the lens of a local study as Derby was albeit briefly the centre of European history. It was there that the rebellion reached its climax, and where the crucial decision to end the invasion of England was taken too. Brian Stone provides a fresh light on the discussions at Exeter House, and how the antipathy of the town and the people of the wider East Midlands played a role in decisions of national importance.

Martyn Bennett

Homes and Places: a History of Nottingham's Council Houses by Chris Matthews.

Published by Nottingham City Homes 2015 £9.99. ISBN 978-0-9934093-0-1 Available from Five Leaves Bookshop, Long Row East

With this book Chris Matthews has presented us with very readable account of a part of Nottingham's social history that is all too often overlooked. The book was commissioned in the spring of 2015 and in a short space of time Chris has managed to read voluminous reports, interview the right people - officials, councillors and others - and collect the thoughts and opinions of existing tenants. The text is enlivened with photographs old and new, mainly from Nottingham City Council, www.picturethepast.org.uk and Nottingham City Homes. The statistics quoted enrich the text and are impressive. There are a few maps and, a very pleasant surprise, a full page reproduction in colour of artist Paul Waplington's May Day Hyson Green 1978. Each of the seven chapters has a comprehensive set of endnotes (references).

The decision to divide the narrative into seven distinct sections is most apt and helps to highlight the changing attitude of central governments to the overall concept of council housing. The seven sections are:

1. The Old Problem

2. Inter-war Success 1919-1939

3. Post-war Rebuilding 1945-1959

4. Clearance and High-rise 1960-1969

5. Clearance and Low-rise 1970-1979

6. Right to Buy, but No Right to Build 1980-2004

7. To Build Again 2005-2015

The chapter headings are really self-explanatory. The Old Problem chronicles the town, pre and post the main enclosure act of 1845 and takes us down to 1914, with just a glimmer of unsubsidised council housing.

Inter-war Success 1919-1939 gives us the twenties, the Cecil Howitt decade, then the thirties with slum clearance and with other architects building on Howitt's high standards, getting national approval!

Post-war Rebuilding 1945-1959 covers the introduction of pre-fabs, steel framed houses and, most important of all, the creation of the Clifton Estate; 6,828 houses were built there for some 30,000 residents in seven years.

Clearance and High-rise 1960-1969: Enter the sixties with central government encouraging high-rise six storeys and above. Various areas in the city, including Basford and Hyson Green were cleared to allow the erection of these towers and deck access blocks.

Clearance and Low-rise 1970-1979: The St. Ann's and the Meadows clearance areas and the 5,500 replacement low-rise houses made the biggest impression on the city's landscape. 14,800 houses were built in the decade, although about half had been started in the 1960s.

Right to Buy but No Right to Build 1980-2004: The 1980 Housing Act drove the 'Right to Buy', at varying levels of discount. The inherent weakness in the Act is shown by the figures: by 2005 only 3,200 new council houses had been built in Nottingham to replace the 20,761 council houses in the city that had been sold. Deck access and high-rise flats had become uneconomic to repair and were unpopular. The demolition of Balloon Woods in 1984 was followed by the Basford Flats, the deck access in Hyson Green and at smaller sites across the city.

To Build Again 2005-2015: To unlock extra funds the Council eventually decided to convert their traditional housing services into one of the new ALMOS - 'arm's length management services' - Nottingham City Homes. After a shaky start it now manages over 28,000 properties for the City Council, still providing those essential back up services; a programme of 'secure, warm, modern' decent homes plus better planned maintenance, by a multi-skilled repair staff. 400 new homes are due to be completed by 2017.

Finally, it is well worth quoting the author's overview on council housing: 'In Nottingham, council housing is popular and widely recognised as something that at one time or another improved the lives of countless people. It is probably safe to add that council housing marked the biggest collective leap in living standards in British history.'

Ken Brand